In the quiet of a forest, a small creature with a bushy tail scampers up an oak tree, its cheeks bulging with acorns. This everyday scene holds within it one of nature's most sophisticated ecological partnerships—the relationship between squirrels and the trees they help propagate. Far from being mere foragers, these agile mammals serve as unwitting foresters, participating in a complex system of seed dispersal that has shaped woodland ecosystems for millennia.

When autumn paints the canopy with fiery hues, squirrels enter their most industrious season. They meticulously harvest nuts, seeds, and cones, often selecting the healthiest specimens through methods scientists are still attempting to fully understand. Their cheek pouches become temporary storage units, carrying multiple items at once as they traverse their territories. This harvesting frenzy isn't merely about immediate consumption—it's about preparation for leaner times ahead.

The true magic of this relationship unfolds in what researchers call "scatter hoarding." Unlike animals that create a single large cache, squirrels distribute their bounty across numerous locations, burying individual nuts or seeds in shallow graves throughout their home range. This behavior creates what ecologists describe as a "living library" of potential forest regeneration, with each buried seed representing a future tree waiting for the right conditions to sprout.

What's particularly fascinating is how squirrels' spatial memory functions. Studies using radio-tracking and observation have revealed that these creatures can remember the locations of thousands of burial sites months after creating them. Their hippocampus—the brain region associated with memory and navigation—shows remarkable development during caching season. Yet despite this impressive recall, a significant portion of these buried treasures remains unretrieved, either forgotten or abandoned due to changing circumstances.

These forgotten seeds become the foundation of forest renewal. Protected from predators and harsh weather in their earthen vaults, they await spring's warmth to germinate. The burial process itself often gives them a better start than if they'd simply fallen to the forest floor. Squirrels typically choose locations with ideal soil conditions, and the act of burial can actually scarify some seeds, helping break their dormancy.

The relationship between squirrels and trees represents a magnificent example of coevolution. Trees have developed traits that encourage squirrel interaction—producing nuts with ideal handling size, maturing seeds at predictable times, and even developing chemical signatures that might indicate nutritional quality. Meanwhile, squirrels have evolved behaviors and physical adaptations that make them exceptionally efficient at harvesting and storing these forest products.

This ecological partnership creates what scientists term a "mutualism"—a relationship where both parties benefit. The trees gain mobile dispersal agents that plant their offspring in ideal growing locations, often at considerable distances from the parent tree. This distribution helps prevent overcrowding and reduces competition among seedlings. For the squirrels, the trees provide a reliable food source that sustains them through winter and early spring when other foods are scarce.

Forest managers increasingly recognize the importance of squirrels and other scatter-hoarding animals in maintaining healthy woodlands. In areas where squirrel populations have declined due to habitat fragmentation or disease, researchers have noted decreased regeneration of certain tree species. Conservation efforts now often include considerations for these furry foresters, ensuring they have the connectivity and resources needed to perform their ecological role.

The impact of squirrel dispersal extends beyond individual trees to shape entire forest ecosystems. By preferentially caching certain species, squirrels influence the composition of future forest generations. Their choices create mosaic patterns of tree distribution, enhancing biodiversity and creating varied habitat structures that support numerous other species. This unintentional landscaping contributes to the resilience and complexity of forest environments.

Climate change introduces new challenges to this ancient partnership. Shifts in seasonal patterns can create mismatches between squirrel behavior and seed availability. Unusually warm winters may reduce the survival advantage of cached food, while extreme weather events can disrupt both the production of seeds and the squirrels' ability to store them. Researchers are closely monitoring how these changes might affect forest regeneration patterns in coming decades.

Urban and suburban environments present another fascinating adaptation of this relationship. City squirrels have modified their caching behaviors to accommodate paved surfaces and human activity. Rather than always burying nuts in soil, they might hide them in flower pots, gutter systems, or other unconventional locations. Despite these adaptations, they continue to perform their ecological role, often planting trees in unexpected places throughout human settlements.

The sophistication of squirrel seed dispersal becomes particularly evident when comparing forests with and without these animals. Studies in areas where squirrels have been absent show different regeneration patterns, often with less genetic diversity and poorer distribution of young trees. This demonstrates how these common creatures serve as keystone species in many forest ecosystems, their activities rippling through the food web and physical structure of the woodland.

Technology continues to reveal new dimensions of this relationship. Using isotope tracing, genetic analysis, and advanced tracking devices, scientists can now follow individual seeds from parent tree to germination site, mapping the intricate networks of dispersal that squirrels create. These studies confirm that a single squirrel may influence the establishment of hundreds of trees throughout its lifetime.

Forest restoration efforts increasingly harness this natural dispersal mechanism. Rather than planting trees manually, conservationists sometimes focus on creating habitat conditions that support robust squirrel populations, allowing these natural engineers to do the planting work. This approach often results in more naturally structured forests with better genetic mixing and appropriate species distribution for the local conditions.

The next time you see a squirrel darting across a park or forest path, consider the invisible threads connecting that small life to the grand tapestry of the woodland ecosystem. In its purposeful movements lie the future of the forest—a testament to how nature's most enduring renewals often come packaged in small, furry containers, scattered with precision and care across the waiting earth.

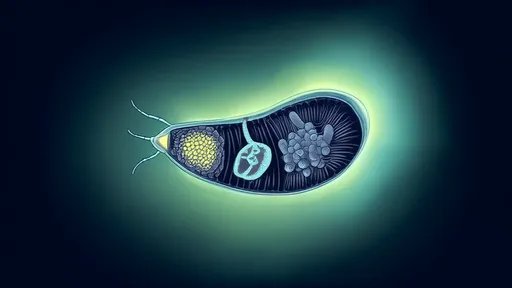

The humble earthworm, often overlooked as it wriggles through the soil, possesses one of nature's most fascinating biological capabilities: regeneration. The idea that an earthworm can be cut in half and both parts will regenerate into complete, living worms has permeated popular understanding for generations. This concept, while rooted in biological truth, is often oversimplified and misunderstood. The reality of earthworm regeneration is a complex dance of cellular biology, environmental factors, and species-specific capabilities that is far more nuanced than the common myth suggests.

In the quiet hours of dawn, as the first light touches the treetops, a familiar sound echoes through the woods—the sharp, rhythmic tapping of a woodpecker drilling into tree bark. To the casual observer, it might seem like a simple search for insects, but this behavior represents one of nature’s most fascinating evolutionary puzzles: how do birds, entirely lacking teeth, process and digest hard, shell-encased foods? From finches cracking seeds to owls swallowing mice whole, birds have developed an array of sophisticated anatomical and physiological adaptations that allow them to thrive on diets that would challenge many toothed animals.

In the quiet corners of forests and the hidden eaves of barns, a master engineer works in silence, producing a material that has captivated scientists and engineers for decades. Spider silk, the unassuming product of one of nature's most prolific architects, possesses a combination of properties that modern science struggles to replicate. Its legendary strength, often poetically compared to being five times stronger than steel by weight, is merely the headline of a much deeper and more fascinating story of biological perfection.

In the quiet waterways of eastern Australia, a creature that seems to defy categorization goes about its daily routine. The platypus, with its duck-like bill, beaver-like tail, and otter-like feet, has long fascinated scientists and laypeople alike. But perhaps its most astonishing feature is one that challenges the very definition of mammalian characteristics: it lays eggs. This peculiar trait, combined with its other unusual biological features, makes the platypus a living repository of evolutionary secrets, offering profound insights into the journey from reptilian ancestors to modern mammals.

The natural world has long captivated human imagination with its dazzling displays of bioluminescence, and among these living lanterns, fireflies hold a special place in both scientific inquiry and cultural fascination. Their ability to produce light through purely biochemical means represents one of nature’s most elegant energy conversion systems. The process by which fireflies transform chemical energy into visible light—a phenomenon known as bioluminescence—is not only a marvel of evolutionary adaptation but also a subject of intense research with implications spanning medicine, environmental science, and bioengineering.

In the eternal battle between humans and household pests, few creatures have demonstrated such remarkable resilience as the common cockroach. These ancient insects have scurried across the planet for millions of years, outliving dinosaurs and surviving mass extinctions. Their continued presence in our homes, restaurants, and cities speaks to an evolutionary success story that both fascinates and frustrates scientists and exterminators alike.

On overcast days when visual landmarks vanish beneath thick clouds, homing pigeons perform a navigational feat that has fascinated scientists for centuries. These remarkable birds can find their way home across hundreds of miles of unfamiliar terrain with uncanny precision. For decades, researchers suspected this ability was tied to Earth’s magnetic field, but the biological machinery behind this “built-in compass” remained one of nature’s most intriguing secrets.

In the profound silence of the deep ocean, a remarkable event unfolds—one that begins with an ending. When a whale dies, its massive body descends through the water column, eventually coming to rest on the seafloor. This process, known as a "whale fall," initiates a complex and enduring ecological phenomenon that can sustain deep-sea life for decades, even centuries. Far from being a mere conclusion, the death of a whale marks the beginning of a vibrant, nutrient-rich oasis in an otherwise barren landscape.

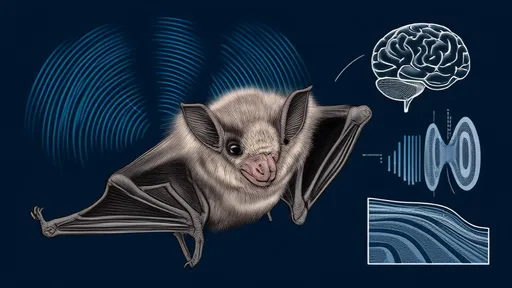

In the shadowy realms of night, where vision falters and darkness reigns, the bat has perfected a navigational art that defies human intuition. For centuries, these enigmatic creatures have sliced through the blackness with uncanny precision, hunting moths and avoiding obstacles with ease. Their secret lies not in superior eyesight, but in an auditory marvel known as echolocation—a biological sonar system that has captivated scientists and engineers alike. This natural innovation has become a cornerstone of biomimicry, inspiring technologies that range from medical imaging to autonomous vehicles. The story of how we have learned to listen to the bats is a testament to nature’s ingenuity and humanity’s relentless drive to innovate.

In the crushing darkness of the deep sea, where pressures defy human comprehension and light is but a distant memory, thrives one of Earth’s most enigmatic creatures: the octopus. With three hearts pumping blue, copper-rich blood and a distributed intelligence spread across nine brains, this alien-like being challenges our very understanding of consciousness, biology, and what it means to be intelligent. The mysteries held within its soft, boneless body may not only rewrite chapters of marine biology but could also force us to reconsider the possibilities of life—both on this planet and beyond.

The ancient wisdom of traditional medicine, passed down through generations of indigenous communities, now stands at a critical crossroads. As the world increasingly turns to natural and holistic approaches to health, the rich pharmacopeia of ethnic and tribal knowledge faces both unprecedented opportunity and existential threat. The protection of this traditional knowledge has become a matter of urgent global concern, particularly as it intersects with the rigorous demands of modern scientific validation.

The realm of biomaterials is witnessing a quiet revolution, one that draws inspiration not from synthetic laboratories but from the intricate designs of the natural world. For centuries, humanity has utilized animal-derived materials like leather, wool, and silk, valuing them for their durability, warmth, and beauty. However, the current wave of innovation moves far beyond these traditional applications. Scientists and engineers are now delving into the molecular and structural blueprints of various creatures, unlocking the secrets to materials with unprecedented properties. This is not merely about using what animals provide; it is about learning from millions of years of evolutionary engineering to create the next generation of advanced materials.

The ancient paradox of poison and medicine has fascinated healers and scientists for centuries. What makes a substance lethal in one context yet therapeutic in another? This question lies at the heart of toxin-based pharmaceutical research, a field that deliberately explores nature’s deadliest compounds as potential sources of life-saving treatments. From snake venoms to bacterial toxins, researchers are increasingly looking toward dangerous biological materials not as threats, but as reservoirs of molecular ingenuity that can be harnessed, repurposed, and transformed into novel medicines.

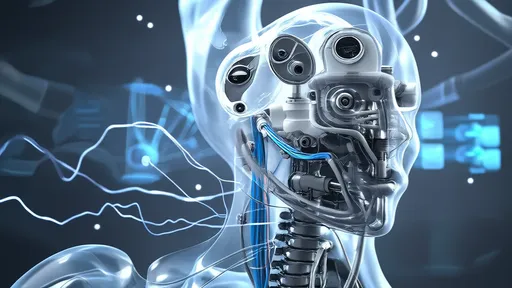

The marriage of biology and engineering has birthed one of the most transformative fields in modern medicine: biomedical devices inspired by nature's designs. This discipline, known as biomimetics or bio-inspired engineering, moves beyond simple imitation. It involves a deep study of biological structures, processes, and systems to create innovative solutions for complex medical challenges. From the intricate architecture of bone to the self-cleaning properties of lotus leaves, nature provides a masterclass in efficiency, resilience, and adaptability. Scientists and engineers are increasingly turning to these biological blueprints to develop the next generation of medical devices that are not only more effective but also more integrated with the human body.

In the vast and intricate tapestry of nature, animals have long served as a source of medicinal compounds, with their unique biochemical arsenals offering a treasure trove for pharmaceutical exploration. The pursuit of novel therapeutics from animal-derived natural compounds represents a fascinating intersection of biodiversity, biochemistry, and modern pharmacology. This field, while challenging, holds immense promise for addressing some of the most persistent human ailments, from chronic pain to antibiotic-resistant infections.

In the quiet of a forest, a small creature with a bushy tail scampers up an oak tree, its cheeks bulging with acorns. This everyday scene holds within it one of nature's most sophisticated ecological partnerships—the relationship between squirrels and the trees they help propagate. Far from being mere foragers, these agile mammals serve as unwitting foresters, participating in a complex system of seed dispersal that has shaped woodland ecosystems for millennia.

In the quiet hours before dawn, while most urban dwellers sleep, a surprising transformation occurs in cities across Europe and Asia. From Berlin to Tokyo, wild boars have begun venturing beyond their traditional woodland habitats, navigating subway tunnels, foraging in city parks, and even establishing residence in suburban neighborhoods. This remarkable adaptation represents one of the most fascinating cases of wildlife successfully exploiting human-modified environments.

The profound stillness of a bear’s winter den belies a storm of physiological activity within. For centuries, the phenomenon of hibernation has captivated naturalists and scientists alike, not merely as a curious behavioral adaptation, but as a masterclass in metabolic regulation. The bear, a consummate hibernator, undergoes a suite of breathtaking physiological changes that allow it to endure months of fasting, immobility, and cold without succumbing to muscle wasting, bone loss, or metabolic disorders that would devastate a human. It is within this state of suspended animation that modern medicine is finding a treasure trove of insights, offering revolutionary clues for tackling some of humanity's most persistent health challenges.

In the dappled light of forest clearings and across the sweeping expanse of tundra, a silent communication network operates with breathtaking efficiency. This is the deer alarm system, a sophisticated web of signals that binds a herd together in a state of perpetual, shared awareness. Far more than just a collection of individuals, a herd of deer functions as a distributed sensory organ, with dozens of eyes, ears, and noses continuously scanning for threats. The survival of each member depends on the instantaneous and accurate relay of information through a language of posture, sound, and scent that is both nuanced and powerfully direct.

In the dense rainforests of West Africa, a remarkable scene unfolds as a community of chimpanzees gathers around a towering nut-bearing tree. An older female, her movements deliberate and practiced, selects a particularly hard-shelled nut, places it on a flat stone anvil, and with a well-worn hammer rock, cracks it open with precise force. Nearby, younger chimps observe intently, some attempting to mimic her technique with varying degrees of success. This transmission of nut-cracking skills from one generation to the next represents more than simple imitation—it is the living heartbeat of cultural tradition in our primate cousins.